[12:58 Sun,9.May 2021 by blip] |

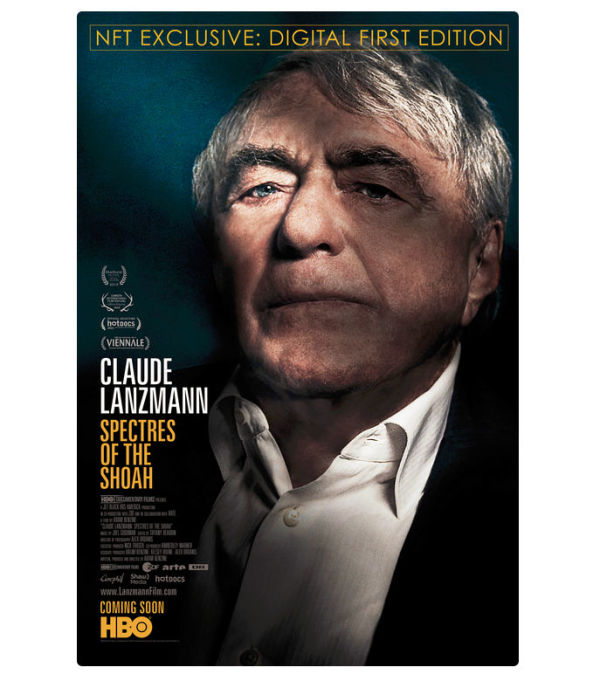

Crowdfunding has largely established itself as an alternative method of film financing. Even if it rarely succeeds in raising larger sums through it, every film project can try to get support from the community in order to be able to realize the project. But to generate enough attention, a lot of PR and communication is needed, and actually, you need a broad fanbase in advance for the campaign to be successful. In fact, crowdfunding is sometimes even used more as a marketing tool than for pure film financing.  Photo Dmitry Demidko Now a new, seemingly absurd financing option is making headlines, with which virtual goods (digital assets), of which there is no original but only copies, can be sold for a lot of money -- digital artworks, photos, videos, Internet memes, properties in virtual worlds, game avatars, whatever. Even a tweet: in March, Twitter founder Jack Dorsey auctioned off his  3 million dollars for a short message that has been around for 15 years and still NFTs run on a blockchain (usually Ethereum) like cryptocurrency, i.e. their "uniqueness" is securitized by means of sophisticated and extremely computationally intensive encryption technology. Unlike Bitcoins, however, this code does not stand for itself, but is linked to a virtual thing. (For a good technical overview of NFTs, see Not only Jack Dorsey&s tweet, but also a digital photo such as How high the scarcity factor is set can be freely determined by the seller - while a work of art might be offered only once, in the music sector albums are sold in special NFT editions (parallel to the very normal distribution channels). They are then bundled with added value, such as additional artwork or a concert ticket subscription. Since these editions are limited, they can gain collector value if there is enough interest in the fanbase. What started in 2017 with the blockchain-based game  For example, Kevin Smith, who became an indie celebrity with his low-budget film Clerks (1994), has caught fire and announced that he will auction off the full distribution rights to his next horror film, Killroy Was Here, as an NFT. He seems less interested in the money than the fact that no one has done this before. The possibility that the hard drives with his film on them might just be lying around in a closet after being handed over, or that the film might simply be recut, doesn&t scare him off, as he tells But also the Oscar-nominated documentary "Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Shoah" will be offered as a limited edition (10 copies), without rights but including some supplements Whether and in what form NFTs can also become an interesting financing option for filmmakers remains to be seen - in principle, of course, any additional source of income is welcome. However, those who are not famous and do not have a fan base will probably have just as hard a time with this as they do now with crowdfunding. In addition, it seems quite possible (as far as we can see) to offer works as NFTs that you didn&t create yourself, which makes this system vulnerable to fraud. Compared to crowdfunding, NFTs also come with a serious disadvantage: because they are based on blockchain computations, they (like cryptocurrencies) generate enormous, invisible power consumption -- auctioning (so-called "dropping") a few short art videos as NFTs gobbles up roughly as much power as the artist consumes in two years of work, to cite an example described by deutsche Version dieser Seite: Hype-Alarm: Filme als NFTs mit Blockchain-Technologie verkaufen und reich werden? |